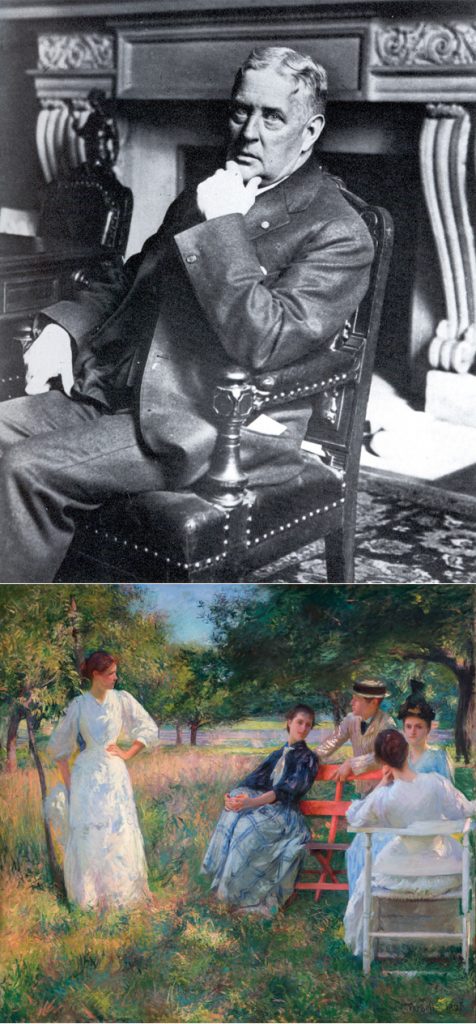

The continued warm weather reminds me there isn’t much more time this season to enjoy the outdoors. The painting In the Orchard by Edmund Tarbell is set in a Dorchester landscape somewhere between Adams Street and Carruth Street.

The paintings of Edmund Charles Tarbell, an American Impressionist, are in many major museums. Edmund Charles Tarbell was born in West Groton, Massachusetts. His father, Edmund Whitney Tarbell, died in 1863 after contracting typhoid fever while serving in the Civil War. His widowed mother, Mary Sophia (Fernald) Tarbell, married David Frank Hartford, a shoe making machine manufacturer and moved with him to Milwaukee, Wisconsin. She left young Edmund and his sister, Nellie Sophia, to be raised by their paternal grandparents in Groton. David and Mary Hartford moved into a new house at 52 Alban St. in Dorchester in 1883.

Edmund Tarbell studied at the Normal Art School, and in 1879, at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts. Tarbell continued his education in Paris, France, then the center of the art world. In 1884-1885, Tarbell traveled to Italy, Belgium, Germany and Brittany. He return to Boston in 1886, he worked as an illustrator, art instructor and portrait painter.

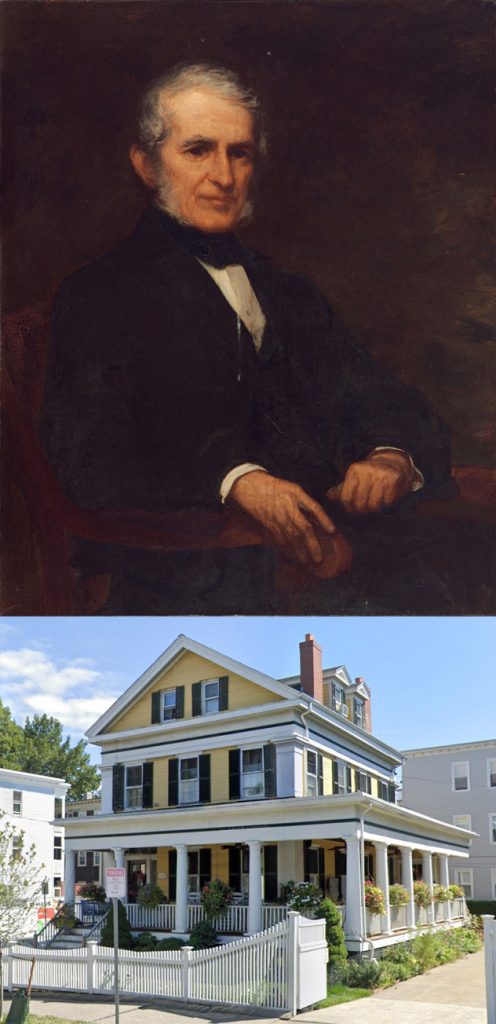

In 1888, at age 26, Tarbell married Emeline Souther, daughter of a prominent family that made its fortune in Quincy and then moved to Dorchester. Tarbell frequently painted his wife and their four children (Josephine, Mercie, Mary and Edmund A.). While teaching at the Museum School in Boston, Tarbell and his family lived most of the time at 24 Alban St. in Dorchester, in a house that belonged to his stepfather. Later they lived at the former Hotel Somerset in Boston, near his atelier in the Fenway Studios on Ipswich Street. In 1905, they bought a summer house in New Castle, New Hampshire, an island on the Atlantic coast, to which he and his wife eventually retired.

“His 1891 painting entitled In the Orchard established his reputation as an artist. Many still consider the work his masterpiece. It depicts his wife with her siblings at plein air leisure. Tarbell became famous for impressionistic, richly hued images of figures in landscapes. His later work shows the influence of Johannes Vermeer, a 17th-century Dutch painter. In such works, Tarbell typically portrays figures in genteel Colonial Revival interiors; the studies of light and quiet are executed with restrained brushwork and color.” http://americanartgallery.org/artist/readmore/id/82