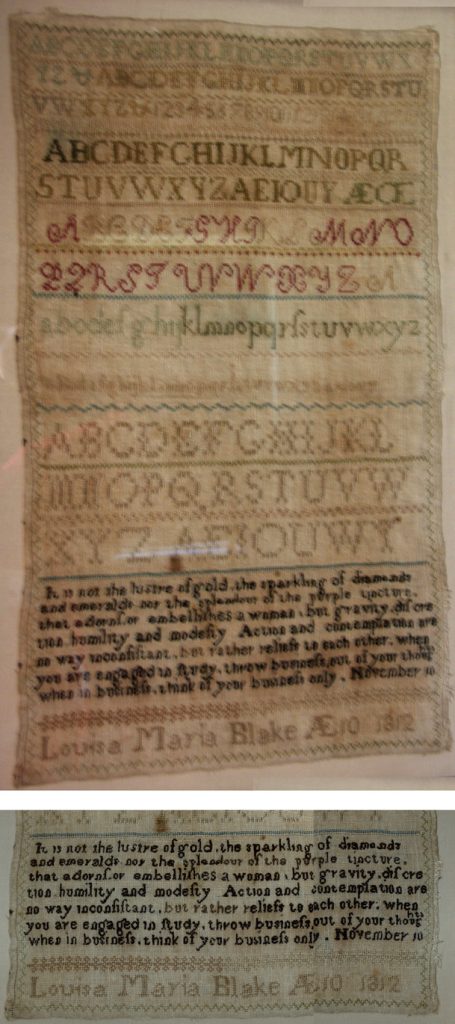

Apologies for the quality of the full image due to the glass over the sampler. The smaller detail avoided some of the glare.

Illustration: sampler made by ten-year old Louis Maria Blake in 1812.

It is not the lustre of gold, the sparkling of diamonds

and emeralds, nor the splendour of the purple tincture

that adorns or embellishes a woman but gravity, discre-

tion, humility and modesty. Action and contemplation are

no way inconsistant but rather reliefs to each other. When

you are engaged in study, throw business out of your thoughts,

when in business, think of your business only. November 10.

Louisa Maria Blake AE10 1812

The first settlers in New England in the seventeenth-century included young women who brought samplers with them to the New World. There are occasional references to the textile arts in early documents, but only very few examples remain. Bed rugs and hearth rugs are some of the extant examples of this early work. The growing sophistication of the colonists over two hundred years in New England resulted in greater demand for decorative arts in the home.

One of the popular types of needlework created by young women was the sampler. Samplers began as a way of recording examples of stitches; therefore, a sampler was an exemplar of the various stitches that a young woman had mastered and wanted to remember. In the twentieth century, we have come to call any needlework signed and dated by the maker by the name of sampler. Perhaps the secret charm of samplers was that they were distinctly the expression of the mind of the girl or her mother or her teacher, and so they are pretty nearly as varied as the mind of man.+ In the second half of the eighteenth century, samplers became more original pieces of work incorporating images of leaves and flowers, houses, dogs and birds, and other scenes from nature.

Most of the known surviving needlework pieces were created by schoolgirls. By the mid-eighteenth century there were many schools serving to round out the education of young women. Some were finishing schools designed to teach the arts of conversation and comportment. Others called themselves academies and offered instruction in languages, reading, geography, and mathematics. Both finishing schools and academies offered needlework instruction as vehicles for religious instruction and for furthering education in mathematics and the basics of the English language.

Much of the emphasis in the curriculum was placed on needlework as evidence of a young woman’s domestic accomplishments. As Americans grew more sophisticated, so too did their style of needlework. Working the alphabet into needlework design began in the seventeenth century. Pictorial embroideries on silk were an eighteenth-century art requiring special technique demanding infinite patience.