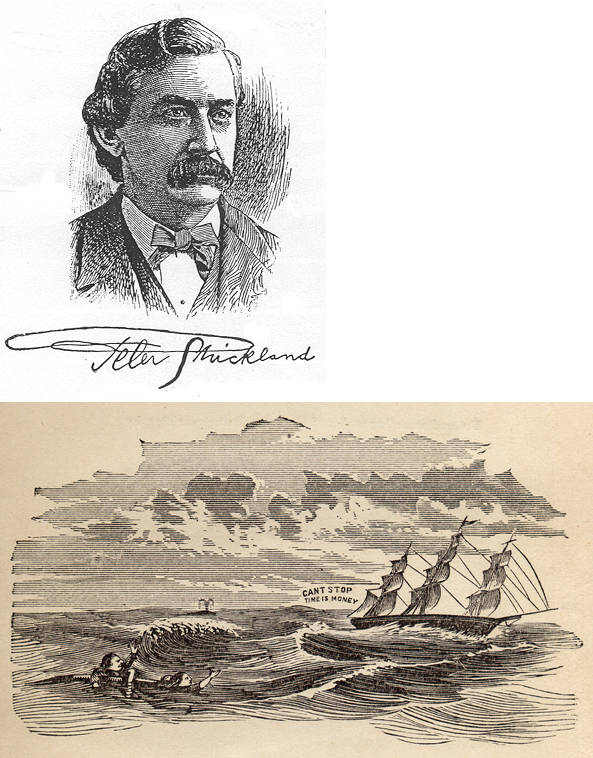

Strickland lived on Neponset Avenue. The illustration is from Captain Strickland’s book A Voice from the Deep.

The following is from Stephen Grant’s website where his book on Strickland is available among Grant’s other books.

Peter Strickland. New London Shipmaster; Boston Merchant; First Consul to Senegal. By Stephen H. Grant. (Washington, D.C., 2007)

Two repositories in the eastern U.S. house important collections of Peter Strickland’s papers: Mystic Seaport Library, Mystic, Connecticut and University of Delaware Library, Newark, Delaware. Papers contain ship logs, business ledgers, 2,000 business and personal letters from 1876 to 1921. Of paramount interest is a personal journal started in 1857 on a journal to Europe at the age of 19. The last entry was in 1921 at the age of 83, where the pen fell from his hand in mid-sentence. The journal is 2,500 pages. In addition, the National Archives and Records Administration in College, Park, Maryland holds the consul’s 272 consular dispatches sent from the French colony of Senegal to the State Department from 1883 to 1905. These handwritten reports are available on 35mm microfilm reels. NARA also possesses 16 bound volumes from Strickland’s period in West Africa, in all 1,850 pages of consular records, many in Strickland’s hand. Strickland authored a book, A Voice from the Deep, published in Boston in 1873. In it, he recounts details of the sailor’s five malefactors: shipping agents, ship owners, boarding masters, ship officers, and . . . consuls.

Strickland claimed he knew more about West African trade than any other American at that time. He made over 40 voyages during the Age of Sail from New England to West Africa, carrying in the holds of his schooners, brigs, and brigantines cargo of leaf tobacco from Kentucky and Tennessee, blocks of ice wrapped up in sawdust from the Kennebec River for refrigeration. The return voyage brought rubber, peanuts, animal hides to be made into shoes and boots, palm oil for cooking, and gum Arabic from the acacia tree for pharmaceuticals, inks, and adhesives.

Because Peter Strickland knew West Africa so well, the administration of President Chester Arthur appointed him consul for French West Africa with domicile on Gorée Island in Senegal, and covering Cape Verde Is., Liberia, The Gambia, Guinea, Bissau, and Sierra Leone. Today we are familiar with consular duties such as screening visa applicants, issuing visas and passports, recording births, marriages, and deaths of Americans, and looking after their whereabouts and welfare. In the 19th century, prime responsibilities were to further American shipping, record shipwrecks and accidents, offer protection to American travelers, report deaths of mariners including loss overboard.

Strickland also reported on rowdy, insolent, and intoxicated sailors. On Feb. 7, 1888, Peter Strickland’s only surviving son George drowned off the coast of Senegal at night. He was in command of the schooner M. E. Higgins on official mission sailing to the coastal town of Saint Louis. He reportedly fell from the rails where he was sitting. The body was never found and the circumstances of his death mysterious. He was 24 years old, a sea captain, and his father’s vice-consul.