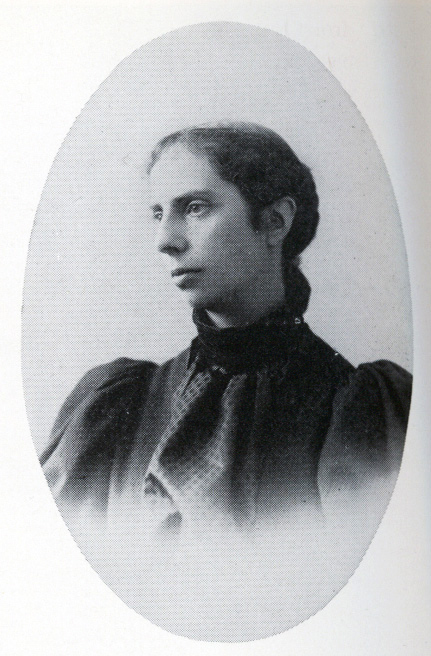

Dorchester Illustration 2590 Alice Stone Blackwell, 1857-1950

The Dorchester Historical Society will host a Zoom program on Sunday, November 6, at 2 pm, about the 50,000 women who registered to vote after the ratification of the 19th Amendment to the Constitution in 1920. The City Archives is working on a databsase of the women, and the project is named the Mary Eliza Project in honor or Mary Eliza Mahoney, the pioneering African American nurse and civil rights activist, who was one of the many women who register to vote in 1920.

To register for the program, please go to the Society’s website www.dorchesterhistoricalsociety.org

Alice Stone Blackwell was the only child of Lucy Stone and Henry Brown Blackwell. After her mother’s death in 1893, Alice carried on her mother’s work for women suffrage as editor the Woman’s Journal.

Alice was educated at the Newburyport, Mass., school of Jane Andrews, at the Harris Grammar School in Dorchester, and later at the Chauncy School in Boston.

Alice described life in Dorchester from her perspective as a teenager in her journal published under the title Growing Up in Boston’s Gilded Age: The Journal of Alice Stone Blackwell, 1872-1874. Alice would catch the train at the Old Colony station at Neponset or at Harrison Square to ride into Boston to exchange books at the Boston Athenaeum or at the Boston Public Library. She would visit her mother at the office of the Woman’s Journal at 3 Tremont Place. On Sundays she would go to church at St. Mary’s Episcopal Church, then on Bowdoin Street, or at the Saint Mary’s Chapel, later the All Saints’ mission at Lower Mills. On school days, Alice would walk toward Harrison Square to attend the Harris School at the corner of Adams Street and Victory Road, formerly Mill Street. Her diary includes descriptions of her walks in the Dorchester countryside –it was still an area of large open spaces, and it was an era when people walked long distances or rode in a carriage pulled by horses.

After Alice’s graduation from Boston University where she excelled and was president of her class, she went to work in the offices of the Woman’s Journal, the paper edited by her mother. Over the next thirty-five years, Miss Blackwell bore the main burdens of editing the country’s leading woman’s rights newspaper–gathering copy, reading proof, preparing book reviews, and writing long columns of crisp, hard-headed arguments for female equality. Beginning in 1887 she also edited the Woman’s Column, a collection of suffrage items sent out free to newspapers round the country. She effected a truce between the American Woman Suffrage Association and Susan B. Anthony’s rival National Woman Suffrage Association. In 1890 the two organizations merged, and Miss Blackwell became recording secretary of the new national American Woman Suffrage Association.

Alice found other evils to expose and underdogs to champion. For years she operated an informal employment service for needy Armenians, and she joined William Dudley Foulke and George Kennan in activating the Friends of Russian Freedom. She translated the poetry of oppressed peoples into English to widen American awareness. Her affiliations widened to include the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, the Anti-Vivisection Society, the Women’s Trade Union League, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and the American Peace Society. Postwar reaction turned her into a socialist radical. One Boston newspaper refused to print her militant letters because of the controversy they provoked. In 1930 she published Lucy Stone, a biography of her mother.

Source: Notable American Women