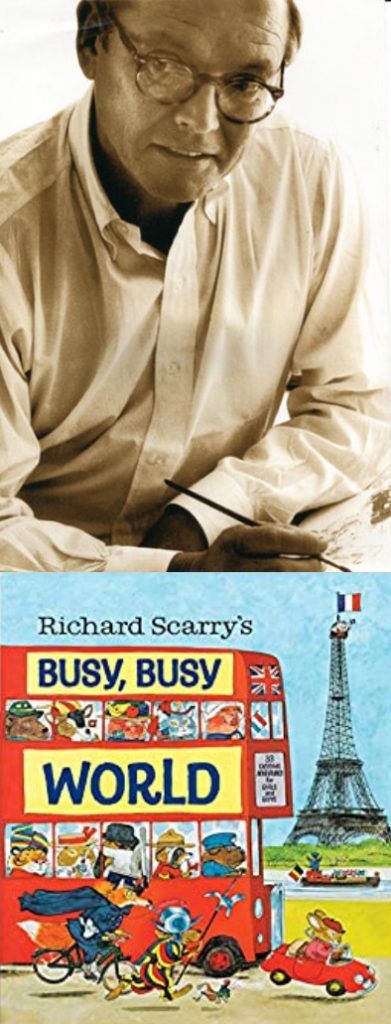

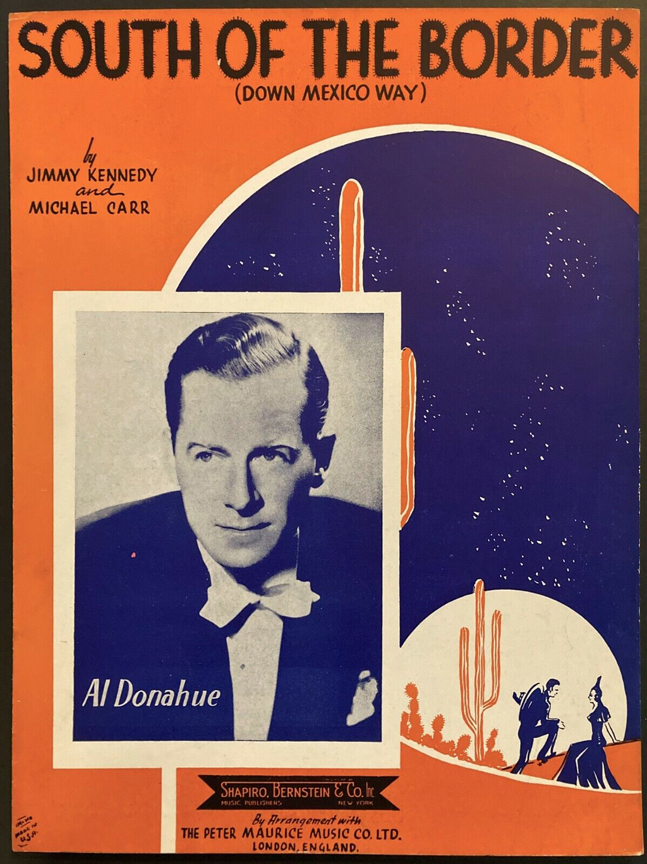

Al Donahue

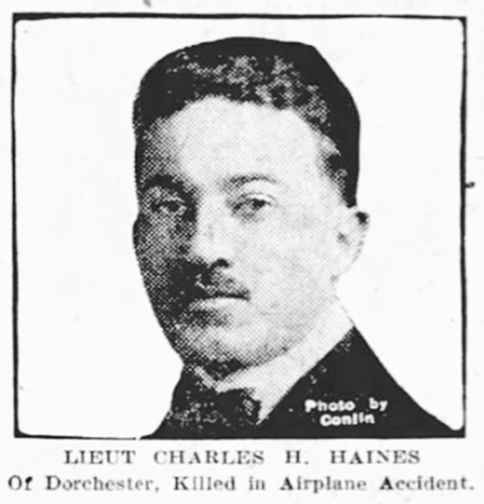

Dorchester Illustration 2620

Al Donahue was a violinist and a big band leader. Albert Francis Donahue was born on Huntoon Street in Dorchester in 1902. He graduated from Boston University Law School, but he was in such demand as a musician, he never took the bar examination. Donahue attended the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston. He got his start playing in Boston-area campus bands.

From the 1930s through the 1950s the Al Donahue Orchestra played at many famous venues across the country including the Rainbow Room of Rockefeller Center in New York City, the Palladium in Hollywood, the Palace Hotel in San Francisco, the Oriental Theater in Chicago, and locally at the Totem Pole in Newton. In 1932, Donahue’s orchestra had provided music aboard Furness Bermuda Line steamship, the Monarch of Bermuda. The orchestra was the featured attraction with regular engagements during 1936-38 at the Bermudiana Hotel in Hamilton, Bermuda.

Between 1935 and 1942, he recorded for Decca Records, Vocalion, and Okeh. His biggest hit was a rendition of “Jeepers Creepers,” which went to number one on the Billboard chart in 1938. He also recorded for University Recording Company. Vocalists including Paula Kelly, Dee Keating, Lynne Stevens, Phil Brito, and Snooky Lanson were guest singers with the band.

After World War II, the ensemble moved away from big band music toward light music, playing throughout the West Coast and appearing in films such as Sweet Genevieve. Later, Donahue would return to cruise ships once more, as music director contracting bands for the Furness Bermuda Line. His band played on the Queen of Bermuda and the Ocean Monarch from 1950 to 1963.

In 1933 he married New York heiress Frederica Gallatin. They had three children, two sons and a daughter. He settled in Oceanside, California, where he ran a store called Ponzi’s House of Music, which closed in the 1970s.

Donahue died in 1983.