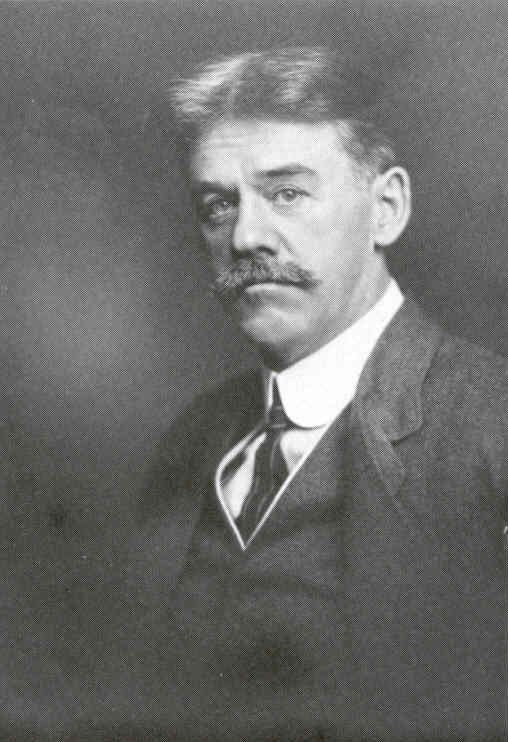

John Fottler and John Fottler, Jr.

Dorchester Illustration 2629

John Fottler, Jr. (1841-1929) came from an agricultural family.

The following is from A Healing Landscape: Environmental and Social history of the Site of Mass Audubon’s Boston Nature Centre. Second edition (Lincoln, MA 2016) page 54.

“Who were the Fottlers? In 1830, Jacob and Barbara Fottler emigrated from Germany to America with their teenage sons John and Jacob Jr. and four other children. Passing through Boston, they originally intended to settle in the Midwest, but tragedy struck: In a much-publicized incident, a steamer sank in the Ohio River at Cincinnati, with Jacob Sr. and two sisters among the dead. Returning back east, the remaining family settled in Dorchester, where John, the eldest son, soon became breadwinner for the family with a job in Quincy Market.

”In 1838, John married Mary Donald, an English immigrant, and the couple began their own family. Making a career in the growing and selling of plants for the needs of the expanding city, John worked in a number of places around Boston; he helped to deliver and plant some of the first shrubs and flowers used in the new landscaping on Boston Common, worked in a nursery in Cambridge, farmed on Savin Hill in Dorchester, and worked his way up to serving as landscaping and agricultural supervisor for various large estates in the area.

“Meanwhile, John’s younger brother Jacob Jr. had married a Hannah Williams of Roxbury and settled on a farm just north of the future BNC, on land now occupied by Franklin Park. Not long after, John and Mary settled with their family on another farm nearby. In the 1870 agricultural census, the Fottlers were the only farmers in the area who sold more garden produce, vegetables and flowers, than did their competitor on Walk Hill Street, Joseph Lambert; and, since John Fottler maintained strong ties to the marketing side of the business, they established a sort of family empire combining both production and distribution in one operation.”

John was called the Father of the Boston Park System. For many years, he lived in a house with the present Franklin Park and owned 21 acres of land there. He broached his plan for the city to purchase the land and induced a committee of the city government to take a look. Mayor Prince wrote to say that posterity would be grateful to him for his service in helping to establish Franklin Park.

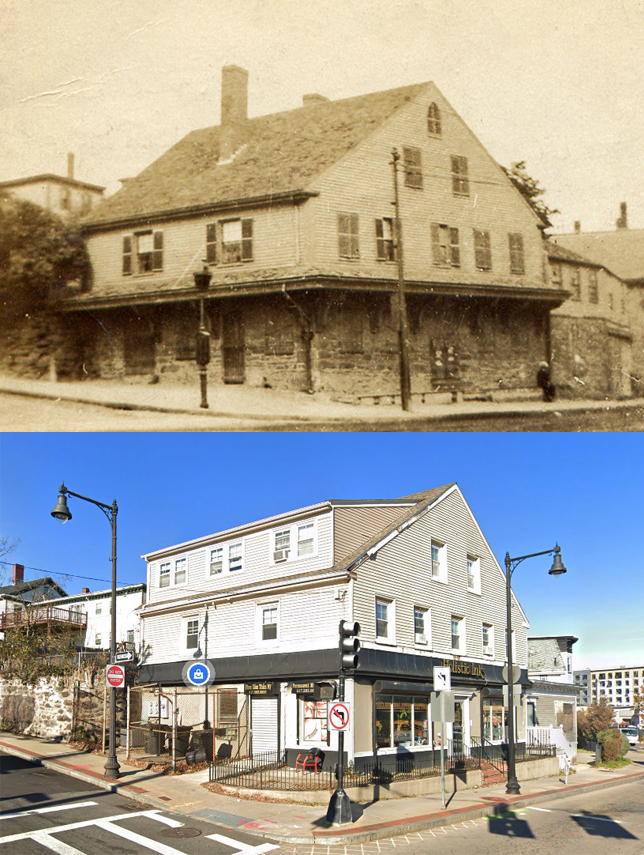

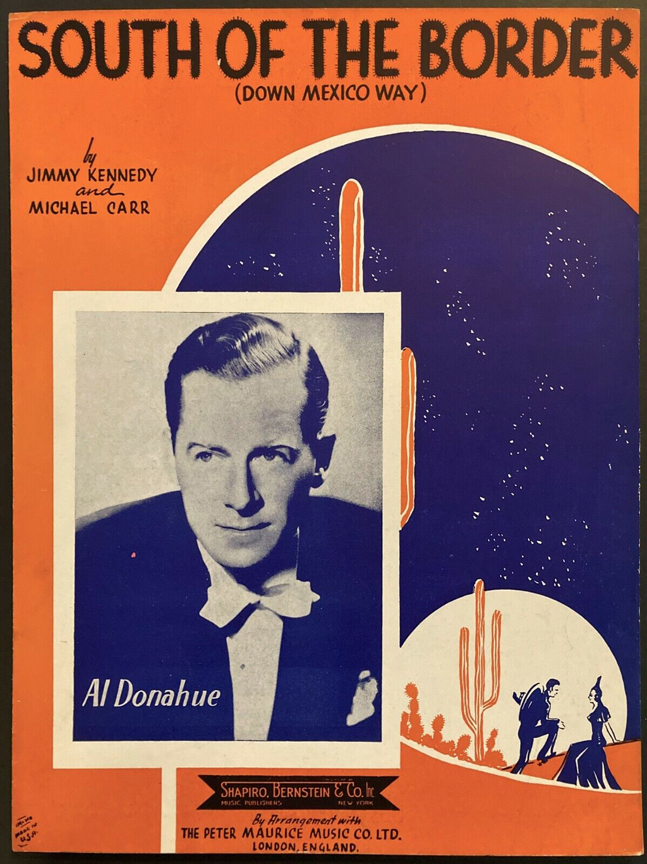

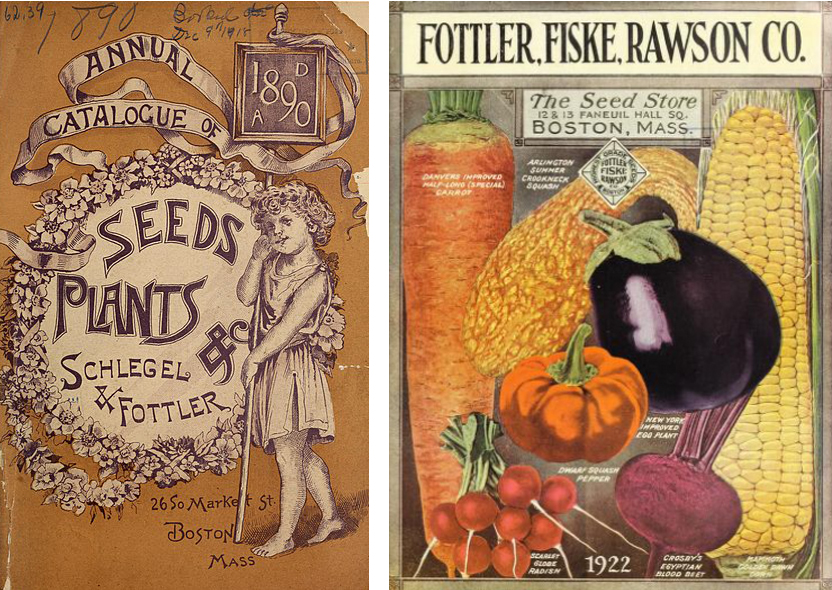

John, Jr., grew up in Savin Hill and established a prominent seed company downtown in partnership with Schlegel, possibly another German immigrant. The firm of Schlegel & Fottler published an annual seed and plant catalog from the 1880s through the first decade of the 20th century. John, Jr., was a founder of another nationally known seed and plant company, the Fottler Riske Rawson Company. John, Jr, had the house at 389 Washington St. built for his home.