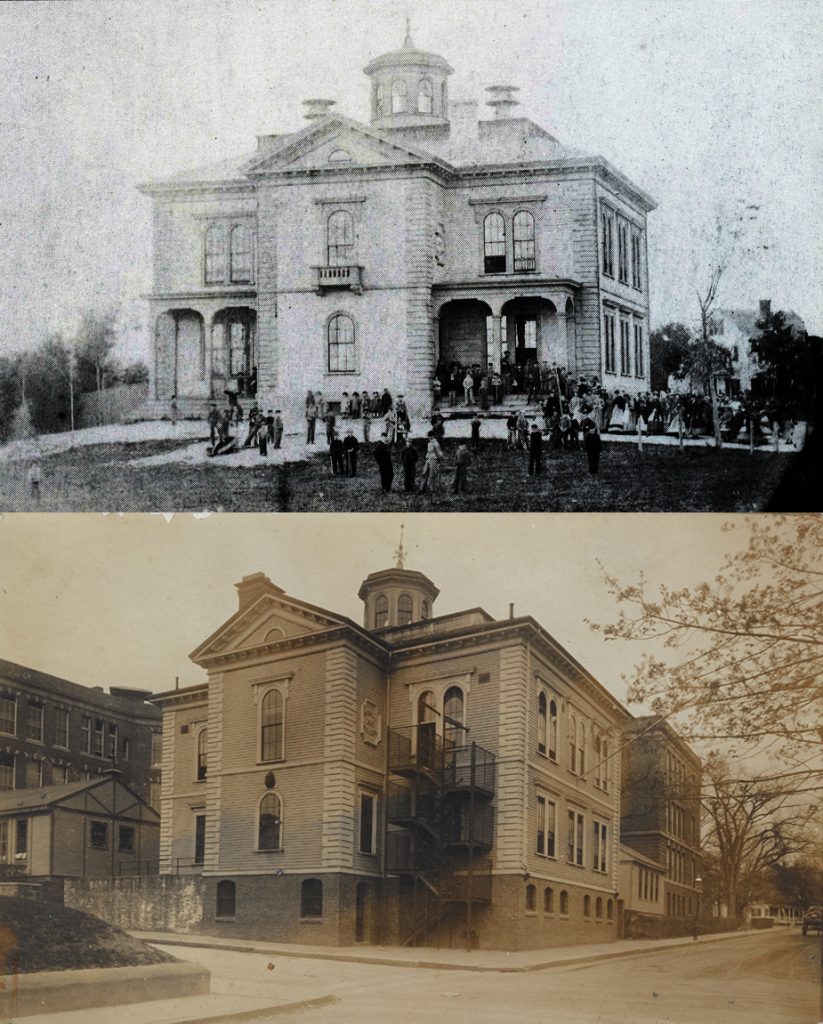

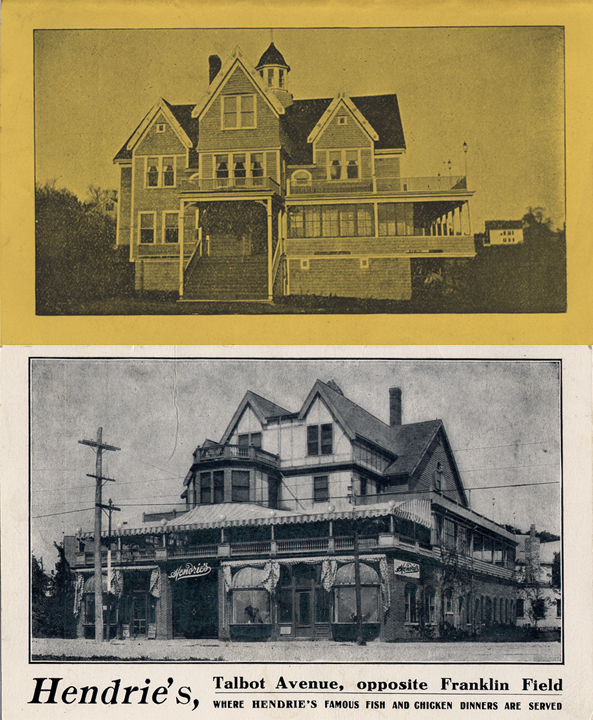

Today’s illustration shows two views of the former Hendrie’s Restaurant, which was located on Talbot Avenue near Blue Hill Avenue. The section of Talbot Avenue from Blue Hill Avenue to Codman Square was laid out in 1888. The building was probably constructed soon after but definitely by the time the Hendrie brothers purchased the property in 1891. The image on the bottom shows a remodeled exterior with a bumped-out first floor and enlargement of the gabled dormer on the right to present a whole new look. The remodeling may have taken place after a fire in 1900.

Hendries Restaurant was located at 22-30 Talbot Avenue across from Franklin Field. It was operated by Joseph A. Hendrie and Robert W. Hendrie. The brothers were born in Scotland and lived at 225 Harvard Avenue when they started their business in 1885. They bought the property on Talbot Avenue in 1891. By 1900, Joseph had moved into the building on Talbot Avenue, while Robert and his family stayed at 225 Harvard Avenue.

Hendries was known for its ice cream. It may have been the company that was purchased by Eliot Creamery in 1930 whose manufacturing facility was in Milton, Massachusetts. Various Hendries Ice Cream signs have the phrase “since 1885,” and that is when Joseph and Robert began their company.

“The Casino at Hendries. “The Casino” at Hendrie’s opened brilliantly Tuesday evening with a large assembly of the Harvard street residents, nearly all the families in this part of Dorchester having some representative, sixty families having accepted the invitation to be present during the season. Tuesday evening the opening night was under the supervision of Mrs. James A. Final and Mrs. Charles A. Young, and consisted of a musicale under the direction of Mrs. Martha Dana Shepard, the well known and popular Boston pianist. The programme rendered was an attractive one, and consisted of a piano duet, Priest’s Mardi from Mendelssohu,by Mrs. Shepard, and her sister Mrs. Searing of Denver, Colorado; tenor solo, “0 Fair and sweet and holy,” Cantor, by Mr. John D. Shepard, son of Mrs. Martha Dana Shepard: piano solo, Scherzo, Bargiel, by Mrs. Searing: duets, ..No Furnace, no Fire,” and “Musical Dialogue” by Miss Goddard and Mr. Sircom: piano solo, Tarantelle, Whitney, by Mrs. Shepard: song, “Proposal” &Brackett, by Mr. John Shepard, song, “Sevilles Grove” by Miss Goddard and solo by Mr. Sircom.

Miss Goddard was in fine voice, and sang her difficult selections with the greatest ease and power. Mr. Sircom was as pleasing as he always is, and his voice blended with Miss Goddard’s in charming melody. Mrs. Shephard played as only she can play, as all who have had the pleasure of hearing her can testify, and her sister Mrs. Searing upholds the reputation of her more widely known sister. Mr. Shepard sang with ease and grace and pleased all his hearers. Mrs. Shepard and Mr. Frank Gilman were the accompanists.

Tables were placed in various corners of the hall where those who were so disposed could indulge in a social game of cards. After the entertainment, dancing was enjoyed by some of the young people, and others repaired to the hall below to refresh themselves with Hendrie’s excellent creams and ices.

The program for Tuesday the 17th, consists of a “Library Party” and will be under the direction of Mrs. J. Jacobs and Mrs. 11. Orcutt.” The Dorchester Beacon, July 14, 1894

The Boston Evening Transcript reported on December 24, 1900 that a fire occurred and nearly destroyed the establishment of Joseph A. Hendrie and his brother at 26 Talbot Avenue. The value of the damage was estimated to be $2,000.

“The Summer Casio parties that were so popular a few years ago at Hendrie’s are to be repeated this season. Subscribers will be sure to have a very enjoyable time in the new ballroom and on the roof garden. The Hendries are doing everything to make their establishment a popular one.” The Dorchester Beacon, July 19, 1902.

By 1903, the brothers had fallen behind in their payments to creditors, and an agreement was reached for extending the payment schedule. The same year, they lost some other property they owned to foreclosure. It is not clear how long the restaurant remained open.

In 2022, a Dollar Tree store occupies approximately the same location.