Dorchester Illustration no. 2472 James John Slater

World War 1 biography

By Camille Arbogast

James John Slater was born on July 1, 1897, at 74 Bromley Street in Roxbury. His father, James Blanchard, a printer, was born in Moncton, New Brunswick; his mother Mary Belle (Campbell) was born in Pleasant Bay, Nova Scotia. James, Sr., and Mary married in Boston in 1894. They had seven other children: Mary Lois born in 1896, George Kenneth in 1899, Mildred in 1900, William in 1902, Edward in 1905, Lillie in 1908, and Irene in 1916. Edward died in 1906 of complications of teething, measles, and possible meningitis.

During James’s childhood his family moved regularly. In 1900, they lived at 53 East Lenox Street in the South End. The next year they moved a few blocks to 44 Lenox Street. In 1902, they relocated again, this time to Jamaica Plain, living at 13 Oakdale Street. They were living in Mattapan in 1904, where they resided at 32 Rockville Street (today’s Rexford Street). By 1906, they had returned to Roxbury, to 2680 Washington Street. In 1907 and 1908 they appeared in the Boston directory back in Dorchester at 14 Johnson Terrace. The 1910 census recorded the family in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, where James, Sr., was the foreman of the pressroom at the New England Automobile Journal. The next year, the Slaters returned to Massachusetts, and lived at 158 Boston Street in Dorchester. Finally, in 1913, they moved to 20 Ballard Street in Jamaica Plain.

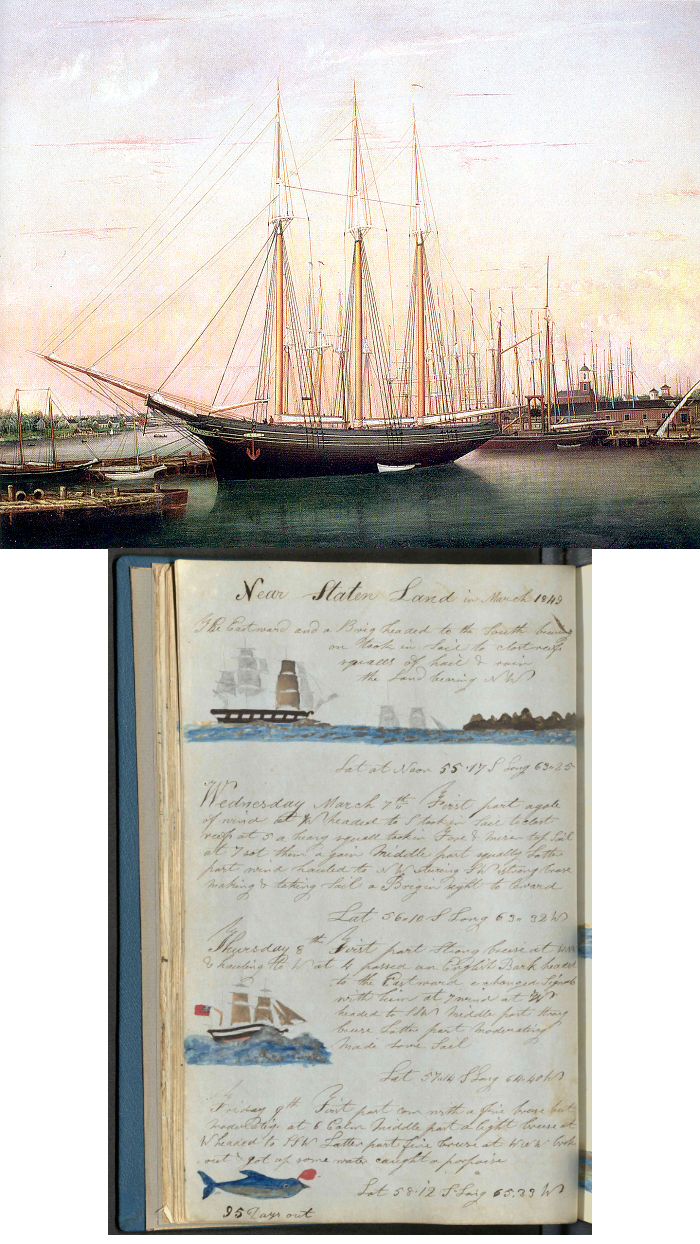

James enlisted in the Massachusetts National Guard on April 6, 1915. He was studying at Northeastern College “when war broke out,” according to a newspaper article. He reported for duty on July 25, 1917, and mustered on July 31, serving as a saddler in Field Hospital #1 of the 26th Division. On September 7, 1917, he sailed for Europe, departing from Hoboken, New Jersey, on the USAT Henry R. Mallory. In October, James was transferred to Field Hospital 104.

In France, James volunteered to participate in a trench fever medical study. According to a newspaper article published after the war, “Trench fever was one of the greatest worries of the medical service of the Allied Armies. At times its ravages incapacitated as high as 40 percent of some combatant units. Almost 90 percent of all sickness in the armies was attributed to this disease.” The illness caused a high fever which lasted a few days, followed by repeated relapses, sometimes recurring for years. The illness could also cause “complications which are either disabling or fatal such as weak hearts, disordered livers or kidneys, bad eye sight, etc.”

The volunteers selected for the experiment were largely from the 26th Division; according to a government publication about the study, the men were drawn primarily “from field hospitals and ambulance organizations, units commonly designated as noncombatant.” James later implied that as a further inducement to participate in the study, men were promised a five-week furlough in the United States. The participants selected had to be extremely healthy and were given a month of “rigorous training” to ensure their bodies were in the best physical shape possible.

In January 1918, James and the other volunteers were transferred to a hospital in Saint Pol, Pas de Calais. The study began in February. Some men were injected with blood taken from trench fever cases; others were infected by lice bite, administered via a box strapped to their arms containing lice collected from the uniforms of trench fever sufferers. Men in the control groups were either subjected to the bites of disease free-lice, or were not exposed in any way but otherwise lived under the same conditions as the rest of the men in the study.

James, participant number 56, was among the men inoculated with infected blood, in his case from “washed blood corpuscle from [participant] No. 35.” In seven days, he was ill with trench fever. First he had a slight headache, which gradually increased, followed by “malaise,” then “pain in back and legs.” After his initial illness, he experienced a “short sharp relapse every six days.” The first and second relapses were more intense than the original attack. During one of his relapses, James reported he felt “depressed as though he could not work.” The next day he was “very miserable yesterday afternoon and through the night with severe headache, backache and shin pains.” With such pain, he had trouble sleeping. Beginning with his third relapse, recurrences of the disease began to decrease in severity. In the midst of the study, the hospital, only six miles from the British front lines, was shelled by the Germans. On March 27, the study had to move to Neuilly.

The study proved that trench fever was an infectious disease primarily transmitted by lice. A government article announcing the study’s findings praised the participants. “It is no mean thing that these volunteers did in France. To face illness of weeks, with extreme suffering, requires peculiar valor. The average loss of weight for these men was from 20 to 25 pounds. … It is believed by the Army Medical Corps that the sacrifice of this group of 66 men will in time lead to the protection of thousands of men from the ravages of trench fever.” General John J. Pershing commended the men, citing them “For exceptionally meritorious and conspicuous services.” Major Richard P. Strong, who led the experiment, “recommended the men for the Distinguished Service Medal.” General Headquarters “refused to award the medal because the service of the volunteers was not of the type which the medal was intended to reward.”

On April 25, 1918, James returned to the 26th Division, “fit for duty,” and was given work as kitchen police. The study checked in on him in early May. He reported he “gets tired easily, and feels that he is not as strong as was a week ago.” He had lumbar pain, especially when he bent forward and stood back up. He remained with the 26th Division, assigned to the 104th and 101st Field Hospitals for the rest of the war. On April 6, 1919, James sailed from Brest, France, on the SS Winifredian, arriving in Boston on April 18, 1919. He was discharged at Camp Devens in Ayer, Massachusetts, on April 29.

After the war, James lived with his family. During his service they had moved to 6 Ripley Road in Dorchester. In 1920, James was a salesman at an electrical company. In the 1920s, James wanted to become an immigration inspector and attempted to take the Civil Service exam. His “disability”—either his exposure to trench fever, or the recurring health problems due to it—were regarded by the government “as too great even to permit him to take the examination.” In 1922, he and his family moved to 145 Bowdoin Street.

On September 16, 1922, James married Alexandra Scott Christie of Allston. Alexandra was a clerk and a graduate of Brighton High School. They were married in Quincy, Massachusetts, by Reverend G. Vaughn Shedd, of the Quincy Atlantic Methodist Episcopal Church. James and Alexandra had a daughter, Phyllis, born in 1923 in South Weymouth.

In the mid-1920s, the Slaters lived in Quincy. At the end of the decade, they moved to the Worcester area, living in Shrewsbury in 1929 and at 51 Institute Road, Worcester, in 1930. James was the manager of an electrical store. By 1931, they had returned to the Boston area and were living in the Wollaston neighborhood of Quincy, where they remained through the 1930s: first at 169 Fenno Street, then 22 Florence Street, and finally 143 Phillips Street.

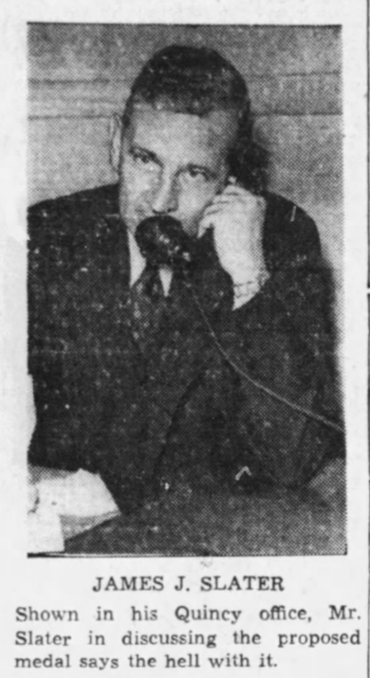

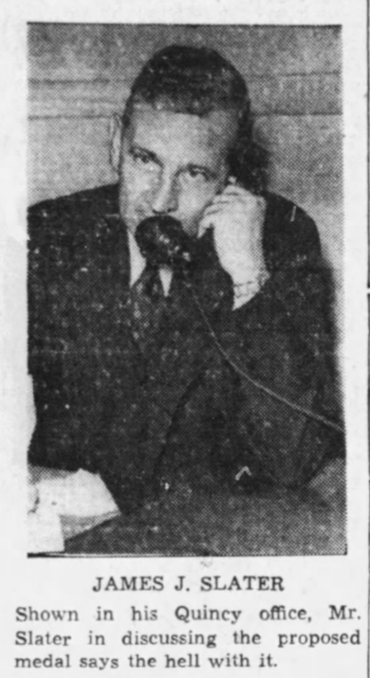

In 1939, Congressman Lawrence J. Connery of Lynn sought official recognition for the trench fever study participants. It seems there was still some uncertainty about how to honor veterans whose contributions were not made on the battlefield. A newspaper article about the Congressman’s efforts explained, “The House Military Affairs Committee wishes to be sure that it will make no mistake if it recommends a medal for [the participants] … Congress wants proof that their service was ‘beyond and above the ordinary call of duty.” In the article, James revealed that over the past twenty years he had continued to experience a “weak back” and “periodic, severe headaches.” James was not interested in any new, special recognition that might be created to honor the men, telling the reporter, “The army recognizes three medals, the Congressional Medal of Honor, the Distinguished Service Cross and the Distinguished Service Medal. Those medals rate with the army and no others do. Now if what we did is worth anything it is worth one of those recognized awards. If it is not worthy of one of those medals it is not worth anything. A special medal, it seems to me, would not mean a thing to anybody, and I say the hell with it. But if they want to give us one of the regular medals, then that is all right. The thing that still makes me sore is that we didn’t get the five weeks furlough to the United States that they absolutely promised us when we volunteered.”

In 1940, James was living on Willow Street in Quincy, employed as a traveling salesman of electrical equipment. At some point, he and Alexandra had divorced. By 1942, he had moved to 113 Commonwealth Avenue in Boston. That year, on his World War II draft registration, he also reported a temporary address: The Braznell Hotel in Miami Beach, where he was staying for business.

In the early 1940s, he married Katherine A. (Muller) Hurley in Boston. Katherine, who had been born in Pennsylvania and grew up in Massachusetts, had also been married before. In the mid-1940s, James and Katherine lived at 61 Sheffield Road in the Newtonville section of Newton, Massachusetts. In the early 1950s, they resided in Brookline, Massachusetts. They then moved to Weston, Massachusetts, where they lived at 7 Columbine Road. In 1962, they relocated to Florida.

James died on May 24, 1969, at the Beach Hospital in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. Funerals were held for him at the Jordan Thomas Garden Chapel in Florida and the Waterman Chapel in Wellesley, Massachusetts. He was buried in Mount Hope Cemetery in Boston. He had been a Past Commander of the FLA, East Coast Chapter- Yankee Division Veterans Association, as well as active with the YD Club of Boston. He was also a member of Masonic Lodge, Dorchester Lodge F. and AM; Knights Templar of Boston, Aleppo Temple; the Royal Order of Jesters Court No 103; and past Patron of Eastern Star, Boston.

Sources

“Massachusetts Births and Christenings, 1639-1915,” database; FamilySearch.org

Family Trees; Ancestry.com

1900, 1910, 1920, 1930, 1940 US Federal Census; Ancestry.com

Boston, Pawtucket, Worcester directories, various years; Ancestry.com

Service Notes

Lists of Outgoing & Incoming Passengers, 1917-1938, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774-1985, The National Archives at College Park, MD; Ancestry.com

Holt, Carlyle. “Vets Who Lost Health as ‘Guinea Pigs,’ Not Keen About Medal Now,” Boston Globe, 12 May 1939; Newspapers.com

“How Sixty-Six U.S. Soldiers Risked Their Lives in Submitting to Trench Fever Tests,” Official Bulletin, Washington DC: Committee on Public Information, 18 June 1918: 1-2; Books.Google.com

Strong, Richard P. Trench Fever: Report of Commission, Medical Research Committee, American Red Cross. American Red Cross Society/Oxford University Press, 1918; Archive.org

“Massachusetts Marriages, 1841-1915,” database; FamilySearch.org.

“Yankee Division Hero Takes Allston Bride,” Boston Globe, 17 Sept 1922: 7; Newspapers.com

Selective Service Registration Cards, World War II: Fourth Registration, National Archives and Records Administration; Ancestry.com

“To These Farewell,” Fort Lauderdale News, 26 May 1969: 13; Newspapers.com

Deaths, Boston Globe, 27 May 1969: 35; Newspapers.com